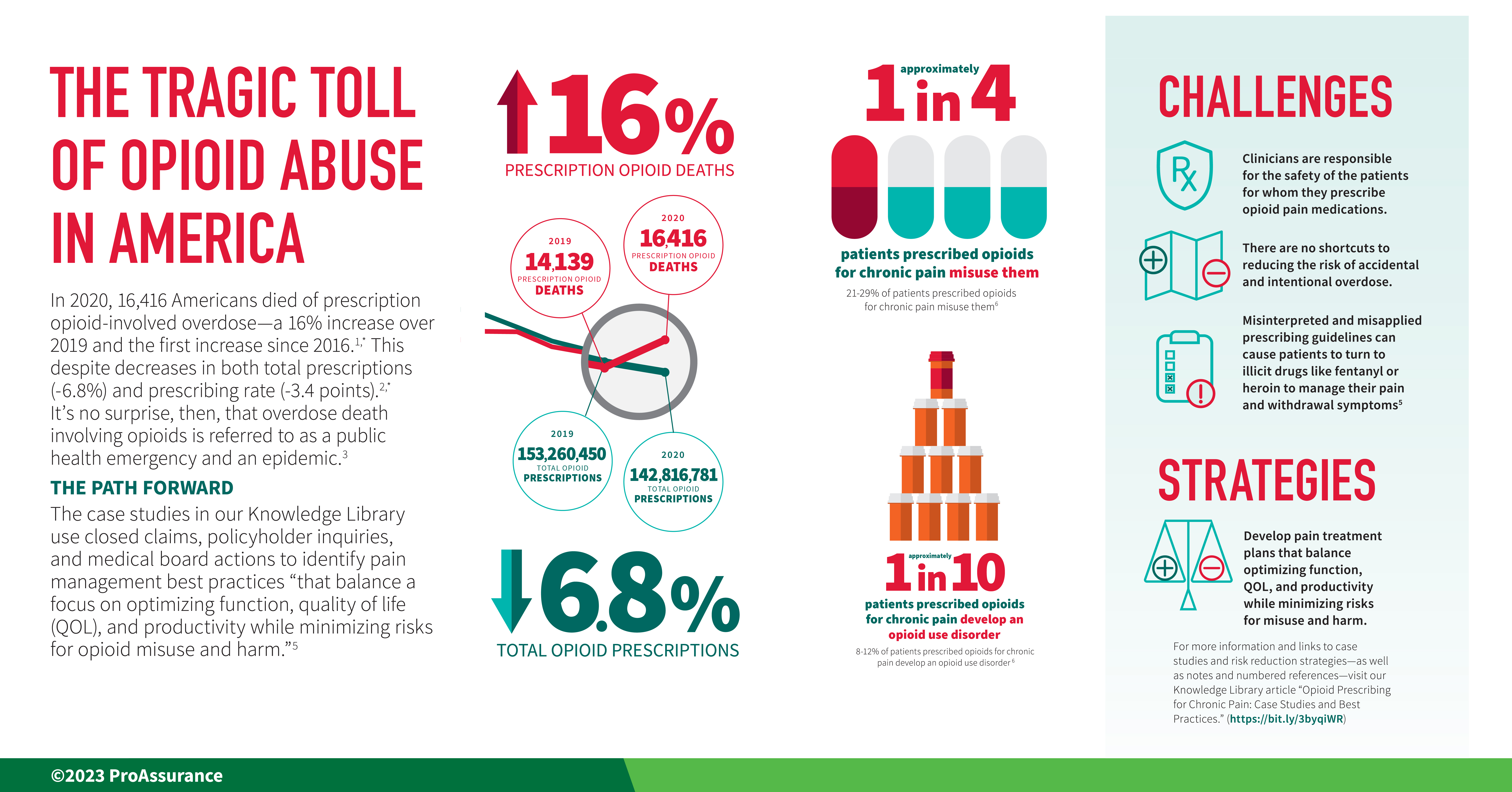

More than 68,000 Americans died of opioid-involved overdose in 2020—a 37.6 percent increase over 2019, and the largest yearly increase in opioid-involved overdose deaths in two decades.1,* A total of 16,416 (23.9 percent) of those deaths involved prescription opioids.1 Approximately 21 to 29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them,2 and between 8 and 12 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain will develop an opioid use disorder (OUD).2 It’s no surprise, then, that overdose death involving opioids is referred to as “a public health emergency” and an epidemic.3,4

Opioid-Involved Overdose Waves and Trending Fentanyl

In recent years, the CDC has described the evolving opioid overdose crisis as three distinct waves in terms of the type of opioid contributing to trends in overdose deaths.5 The First Wave saw increased opioid prescribing in the 1990s and increasing overdose deaths involving prescription opioids “since at least 1999.”5 In 2010, heroin overdose deaths began to rise, marking the beginning of the Second Wave. The current Third Wave began in 2013 with a dramatic rise in synthetic opioid (particularly illicit fentanyl)† overdose deaths.5 The data show just how much synthetic opioids/fentanyl are driving recent trends in overdose deaths as of 2020:1

- 82.3% of all opioid overdose deaths

- 61.6 % of all overdose deaths

- 55.4% increase over 2019

- More than heroin, cocaine, and psychostimulants/methamphetamine‡ combined

Although the death rates for prescription opioid overdose are lower than death rates for synthetic opioids—over which healthcare providers have little direct influence—research seems to indicate that some patients who abuse prescription opioids will at some point transition to illicit opioids such as fentanyl and heroin.6 Consequently, there are good reasons for opioid prescribers to remain vigilant about carefully balancing the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain.

Although the death rates for prescription opioid overdose are lower than death rates for synthetic opioids—over which healthcare providers have little direct influence—research seems to indicate that some patients who abuse prescription opioids will at some point transition to illicit opioids such as fentanyl and heroin.6 Consequently, there are good reasons for opioid prescribers to remain vigilant about carefully balancing the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain.

Public awareness campaigns and clinician compliance with opioid prescribing guidelines such as the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain appear to be resulting in reductions in patient exposure to prescription opioids.7 However, the 2016 Guideline has been misinterpreted and misapplied8 by some physicians, resulting in chronic pain patient abandonment, medication discontinuation, and forced tapering.7 These situations can cause patients to turn to illicit drugs like heroin to manage their pain and withdrawal symptoms, or alternatively to commit suicide.7

In the years since the 2016 Guideline came out, the CDC and others have published reports, commentaries, and guidelines that should reduce some of the confusion surrounding pain management in patients for whom opioid therapy is appropriate. In November 2022, the CDC also released their new Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain, which updates and replaces the 2016 Guideline.

In the years since the 2016 Guideline came out, the CDC and others have published reports, commentaries, and guidelines that should reduce some of the confusion surrounding pain management in patients for whom opioid therapy is appropriate. In November 2022, the CDC also released their new Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain, which updates and replaces the 2016 Guideline.

According to the CDC, the new Guideline “reflects updated evidence and research on the risks and benefits of prescription opioids for acute, sub-acute, and chronic pain, opioid dosing strategies and dose-response relationships, opioid tapering and discontinuation, comparisons with non-opioid pain treatments, and risk mitigation strategies” and the CDC recommends it for “clinicians providing pain care, including those prescribing opioids, for outpatients 18 years or older.”

NORCAL Group claims involving opioid therapy in chronic pain management patients generally involve overdose deaths. Allegations supporting negligence claims against physicians include: excessive opioid prescribing; failure to refer the patient for pain management, addiction, or behavioral health treatment; failure to discover the patient was doctor shopping; failure to recognize suicide risk; and negligent tapering. The linked case studies use NORCAL Group closed claims, policyholder inquiries, and a recent medical board action to support “pain treatment plans that balance a focus on optimizing function, quality of life (QOL), and productivity while minimizing risks for opioid misuse and harm.”7

NORCAL Group claims involving opioid therapy in chronic pain management patients generally involve overdose deaths. Allegations supporting negligence claims against physicians include: excessive opioid prescribing; failure to refer the patient for pain management, addiction, or behavioral health treatment; failure to discover the patient was doctor shopping; failure to recognize suicide risk; and negligent tapering. The linked case studies use NORCAL Group closed claims, policyholder inquiries, and a recent medical board action to support “pain treatment plans that balance a focus on optimizing function, quality of life (QOL), and productivity while minimizing risks for opioid misuse and harm.”7

COVID-19 and Opioid Use Disorder

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, people may not have noticed the March 18, 2020, CDC press release that led with the news that overall overdose death rates decreased from 2017 to 2018 in the United States, with a significant portion of the decrease attributed to reductions in prescription opioid-related deaths.9 Unfortunately, opioid deaths began increasing again after 2018 and especially in 2020, due in part to COVID-19.1,10

COVID-19 also disrupted OUD treatment.11 For example, social distancing complicated the ability of individuals to engage in peer-support groups and obtain methadone and other medications that treat addiction. Since social isolation can also contribute to the development and exacerbation of OUD, lock-down orders may have also contributed. In addition, a person who overdoses alone has no one to administer naloxone.12 The good news is that government agencies made some exceptions during the pandemic to facilitate OUD treatment; see, for example, the DEA COVID-19 information page and the SAMSA Opioid Treatment Program Guidance.

COVID-19 also disrupted OUD treatment.11 For example, social distancing complicated the ability of individuals to engage in peer-support groups and obtain methadone and other medications that treat addiction. Since social isolation can also contribute to the development and exacerbation of OUD, lock-down orders may have also contributed. In addition, a person who overdoses alone has no one to administer naloxone.12 The good news is that government agencies made some exceptions during the pandemic to facilitate OUD treatment; see, for example, the DEA COVID-19 information page and the SAMSA Opioid Treatment Program Guidance.

While studies centered on measuring the effects of the pandemic on opioid deaths are beginning to emerge,13 overdose deaths increased in 2020 for many other prescription and illicit drugs tracked by the CDC.1 It thus seems likely that the pandemic may have contributed to increased drug misuse generally.1

Additional Resources

American Society of Addiction Medicine “Guidelines: COVID-19 Resources”

A collection of addiction medicine resources and webinars addressing different issues associated with addiction treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic to aid clinicians

An article in which four related factors are considered to help guide healthcare professionals caring for patients with chronic pain during the pandemic: 1) the public health consequences of COVID-19 for patients with pain; 2) the consequences of not treating these patients for the unknown duration of this pandemic; 3) options for remote assessment and management; and 4) clinical evidence supporting remote therapies

Clinicians are responsible for the safety of the patients for whom they prescribe opioid pain medications. There are no shortcuts to reducing the risk of accidental and intentional overdose. These patients require various assessments, treatment plans that maximize the use of non-opioid treatments, monitoring, and referral when appropriate. A thorough informed consent process that covers the risks associated with opioid use, the expected benefits, uncertainties of the anticipated treatment plan, and the alternatives is an essential aspect of pain management that includes opioid therapy.

Patients who can taper their opioid use probably have a lower risk of overdose and may even experience reduced pain.8 Interested and motivated patients should be supported with a plan to slowly taper opioid dosages. Patients with OUD should be offered medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and patients who continue to take high-dose opioids should be closely monitored to mitigate overdose risk. In the unfortunate event that a patient dies of an overdose, documentation proving reasonable patient safety efforts and compliance with state opioid prescribing statutes and regulations will provide evidence of treatment consistent with the standard of care.

More Information About Opioid Prescribing for Chronic Pain

|

Page Notes & References

Notes

* Comparisons calculated from source data in cited references

† Synthetic Opioids other than Methadone (primarily fentanyl)

‡ Psychostimulants with Abuse Potential (primarily methamphetamine)

References

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Overdose Death Rates.” January 20, 2022. Source: Linked data file overdose_data_1999-2020-5.16.22.xlsx.

2. Kevin E. Vowles, Mindy L. McEntee, et al. “Rates of Opioid Misuse, Abuse, and Addiction in Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Data Synthesis.” Pain. 2015 Apr;156(4):569-576. DOI: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1.

3. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “Ongoing Emergencies & Disasters.” Page last modified October 6, 2022.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “What is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic?” Content last reviewed on October 27, 2021. (page no longer available as of the date of publication)

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Opioid Data Analysis and Resources.” Page last reviewed: June 1, 2022.

6. Julia Dickson-Gomez, Sarah Krechel, et al. “The Effects of Opioid Policy Changes on Transitions from Prescription Opioids to Heroin, Fentanyl and Injection Drug Use: A Qualitative Analysis.” Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2022 Jul 21;17(1):55. DOI: 10.1186/s13011-022-00480-4.

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. 2019.

8. Deborah Dowell, Tamara Haegerich, et al. “No Shortcuts to Safer Opioid Prescribing.” The New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380:2285-2287. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1904190.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “New Data Show Significant Changes in Drug Overdose Deaths.” Press Release. Page last reviewed March 18, 2020.

10. Andis Robeznieks. “COVID-19 May Be Worsening Opioid Crisis, But States Can Take Action.” American Medical Association. May 28, 2020.

11. Nora Volkow. “COVID-19: Potential Implications for Individuals with Substance Use Disorders.” National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). April 6, 2020.

12. Peter Grinspoon. “A Tale of Two Epidemics: When COVID-19 and Opioid Addiction Collide.” Harvard Health Blog. April 20, 2020.

13. Rina Ghose, Amir M. Forati, et al. “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Opioid Overdose Deaths: a Spatiotemporal Analysis.” Journal of Urban Health. 2022 Apr; 99(2): 316–327. DOI: 10.1007/s11524-022-00610-0.

Infographic Notes & References

Notes

* Comparisons calculated from source data in cited references.

† Prescription rate is retail opioid prescriptions dispensed per 100 persons

‡ Death rates are age-adjusted per 100,000 population.

References

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Overdose Death Rates.” January 20, 2022. Source: Linked data file overdose_data_1999-2020-5.16.22.xlsx.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “U.S. Opioid Dispensing Rate Maps.” Page Last Reviewed: November 10, 2021.

3. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “Ongoing Emergencies & Disasters.” Page last modified October 6, 2022.

4. Julia Dickson-Gomez, Sarah Krechel, et al. “The Effects of Opioid Policy Changes on Transitions from Prescription Opioids to Heroin, Fentanyl and Injection Drug Use: A Qualitative Analysis.” Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2022 Jul 21;17(1):55. DOI: 10.1186/s13011-022-00480-4.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. 2019.

6. Kevin E. Vowles, Mindy L. McEntee, et al. “Rates of Opioid Misuse, Abuse, and Addiction in Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Data Synthesis.” Pain. 2015 Apr;156(4):569-576. DOI: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1.